|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Fertility and Renewal: The Yezidi New Year Festival Sere SalSere Sal festival honors ancestors and the ‘Fiery Bird’ Tawûsê Melekby Nallein Satana Al-Jilwah Sowilo

|

Tawûsê Melek is depicted as a peacock. |

"Say then, Let the Light of Knowledge flash forth from the ziarahs,

Flash forth from the river of Euphrates to the hiddenness of Shambhala!

Let My sanjak be carried from its safe place into the Temple,

And let all the clans of Yezid know of My Manifestation!"

-Revelation of Tawûsê Melek (Qu'ret al-Yezid)

Yazidis believe that Tawûsê Melek the 'Peacock Angel' is the representative of God on the face of the Earth, and that he comes down to the Earth on the first Wednesday of Nisan (April). Yazidis hold that God created Tawûsê Melek on this day, and observe it as New Year's Day, a time of remembrance, renewal, and fertility. |

Fertility and the renewal of life play a central role in Yezidi religious thought and practice. It is therefore natural that their festivals embody life-affirming religious ideas as ancient as humanity itself. No Yezidi festival better illustrates this than the New Year festival Sere Sal, the spring fertility festival of annual renewal that symbolizes the story of creation, of immortality, death, rebirth and incarnation, in the renewed cycle of life and fertility.

The Yezidi New Year festival Sere Sal (literally ‘head of the year’) is celebrated on Charshema Sor or ‘Red Wednesday’, the first Wednesday after April fourteenth. Sere Sal commemorates a remote time when the ‘Peacock Angel’ Tawûsê Melek descended to earth to spread his brilliant wings in order to calm the lifeless earth from its agitation and to bless the earth with peace and fertility as represented by the peacock, the rainbow, and their bright colors. It is the oldest surviving feast in Mesopotamia.

Charshema Sor, when all work ceases, is a day of rest, reflection and worship. The celebrations begin on Tuesday evening, when the glow of candles and lamps fills Lalish Valley to welcome the New Year, announcing the birth of spring and the new cycle of life and rebirth.

|

The colors of the eggs, including red, blue, green and yellow, represent the rainbow created by Tawûsê Melek when he descended at Lalish on Charshema Sor to bless the earth with fertility and annual renewal. |

Sere Sal celebration includes the coloring of eggs, a tradition often associated with Easter that actually dates back much earlier to the spring festival of Ishtar, the moon goddess of love, fertility, and war, who was the most widely worshiped goddess in Babylonian and Assyrian religion. On the first day of the festival of Ishtar, the Assyrians would hang dyed eggs from the temple walls, signifying the fertility of Ishtar. Ishtar may be etymologically connected to Eostre, the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring whose name later gave rise to modern the English word 'Easter'.

|

Red poppy flowers that bloom only in April are gathered to bless Yezidi homes with good luck and to bless young couples with fertility. |

In Yezidi thought, the colors of the eggs, including red, blue, green and yellow, represent the rainbow created by Tawûsê Melek when he descended at Lalish on Charshema Sor to bless the earth with fertility and annual renewal. Yezidi homes are also marked with the colored eggshells and with red flowers that bloom only in April to bless the homes with good luck, and to bless young couples with fertility.

As Eszter Spät, the author of Late Antique Motifs in Yezidi Oral Tradition and Yezidis observes:

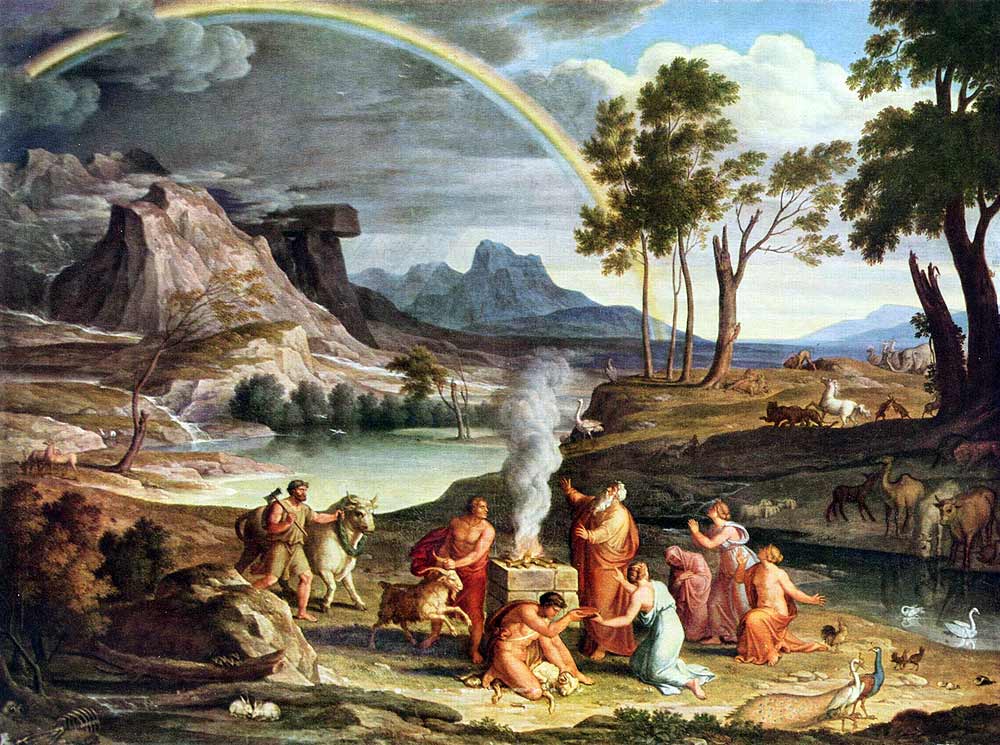

The Rainbow created by Tawûsê Melek when he descended at Lalish on Charshema Sor is also a symbol in ancient cultures of the Heavenly Bridge or covenant that units all life with its ultimate Source. In Semitic tradition, for example, after being delivered from the Flood, Noah builds an altar to the Lord. God then sends the rainbow as the sign of this "everlasting covenant between God and every living creature of all flesh that is on the earth" [Genesis 9:12-17].

|

|

Noah's Thanksoffering (c.1803) by Joseph Anton Koch. Noah builds an altar to the Lord after being delivered from the Flood; God sends the rainbow as a sign of His covenant. |

|

Yet there are times when He reveals Himself in all His brilliant splendor, like a rainbow following a great storm. |

|

A Yezidi cemetery located on the heights of Sheikhan |

Likewise for Yezidis, the rainbow with its seven colors is a manifestation of Tawûsê Melek, a reminder that although the Peacock Angel remains out of sight most of the time, yet there are times when He reveals Himself in all His brilliant splendor, like a rainbow following a great storm. Therefore whatever offerings Yezidis may make to their ancestors, as on Charshema Sor, primarily those offerings are made with the intention that Tawûsê Melek, God's regent on earth, may through his beneficient influence renew and restore the fertility of the earth, including crops, livestock, and most especially the fertility and welfare of the Yezidi people themselves.

An important feature of Sere Sal concerns the motifs of fire, the sun, and the return of departed ancestors, including especially Tawûsê Melek the Peacock Angel himself. Yezidis believe that the spirits of the dead return to their graves on Red Wednesday, because their ancestors died with the firm intention of celebrating every Sere Sal, as the faeries and other spirits of the earth are likewise believed to gather at this time. Yezidis accordingly do not fear the graveyards of their own ancestors, but come out to welcome, greet, and share food offerings, dance and music to the spirits of the departed, the living, and those who are yet to appear.

Before dawn on the day of Charshema Sor, women dress up in colorful clothing and go to nearby cemeteries with dishes, sweets, lamps and other offerings for the dead and fairy spirits who are said to return to earth on Charshema Sor. These offerings include oranges, apples, dates, and colored eggs, etc. The graves are transformed into banquets for the departed who return to their graves. Women sing and dance with dehol (drum) and zorna (shawm). Tablecloths are spread on the ground between the graves as the women also feast upon their offerings. The graves are also decorated with painted eggs and a red flower that can be found only in April. Meanwhile, back in the villages, the men congratulate each other at the beginning of the New Year.

|

Yazidi women light candles and torches outside Lalesh temple during a ceremony to celebrate the Yazidi New Year, on 17 April 2007. Inset: The Peacock Angel Tawuse Melek |

That day, cattle are garlanded with flowers in honor of Memyshivan, the protector of cattle. This too is done to bestow fertility upon Yezidi livestock.

That night a great bonfire is lit at Lalish to beckon Tawûsê Melek to return as the sun, for both God and the sun are considered to be fiery by nature, and therefore fire is considered sacred. Compare this to Hebrews 12:29 "For our God is a consuming fire." Fire is regarded as an earthly form of the divine energy of the ‘Fiery Bird’ Tawûsê Melek.

It is said that boiling eggs at Sere Sal time represents how the earth was at first liquid and only then became solidified at Lalish. Marriage is forbidden during the month of Nisan while the earth is springing to life. Also forgiveness is enjoined at this time. Many who have been adversaries reconcile with mediation by a priest or friend for the sake of the New Year. This too reflects the Sere Sal theme of renewal and a fresh beginning.

‘Procession of the Peacock’

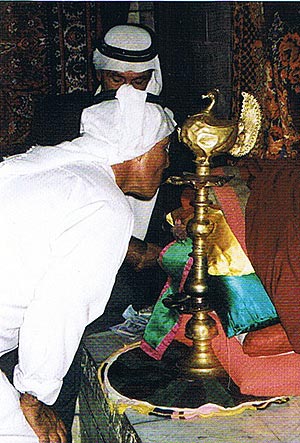

Another very important observance of the Sere Sal season is called the ‘Parade of the Sanjak’ or ‘Procession of the Peacock’, when the sanjaks or peacock lamps representing Tawûsê Melek are taken from their normal home, the residence of the Yezidi prince, and are conducted in stately processions from one Yezidi village to another accompanied by qawals, the sacred minstrels who offer traditional songs praising the Peacock Angel. As the sanjak is taken in procession, the faithful offer flowers, prayers, rich meals and sweets to the Peacock Angel and His traveling entourage.

At night the sanjak is watched over by a mir (priest) and by qawals who attend to the worship of Tawûsê Melek throughout the night. The sanjak is blessed with sacred oil and frankincense, offered incense and holy Zam Zam water. The holy spring of Zam Zam in Lalish dates back to Zoroastrian times.

There are seven sanjaks in total, each representing six great angels and Tawûsê Melek. The largest and most important one is the Sheikhni, representing Tawûsê Melek. At night a mir, the representative of Tawûsê Melek, attends to the sanjaks with prayers, and offerings of incense and oil are made followed by rounds of music and song about Tawûsê Melek throughout the night.

|

The Sheikhani sanjak displayed at Lalish. Photo by Eszter Spät |

|

The tomb of Sheikh ʿAdī, draped with brightly colored satin cloths, appears as a peacock or a rainbow. |

|

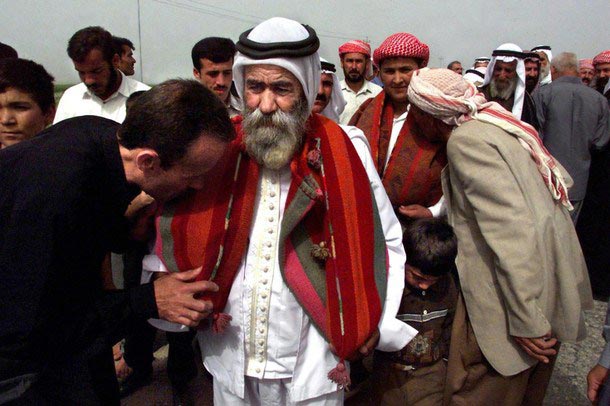

The current Baba Sheikh, Khurto Hajji Ismail |

On the evening of Sere Sal after the Parade of the Peacock is concluded, Yezidi spiritual leaders including the Baba Sheikh assemble in the temple at Lalish. Meanwhile, thousands of Yezidis gather outside holding small oil lamps. The Baba Sheikh enters the tomb of Sheikh ʿAdī where he drapes new rainbow-colored satin cloths upon the tomb. He then lights a lamp and offers up incense and murmurs a special prayer addressed to Tawûsê Melek in the person of Sheikh ʿAdī.

Yezidi faithful crowd together in the small courtyard of Lalish sanctuary waiting for the Baba Sheikh to emerge, holding thousands of lit lamps. A hush comes over the multitude as the Baba Sheikh emerges and recites the 'Moon Dawn' prayer Nivea Nivro in which Tawûsê Melek the Peacock Angel says, "My wisdom knoweth the truth of things and my truth hath mingled with me...indeed I am He that pervadeth the highest heavens and I am He that cries in the wilderness." At dawn they pray Niveja Beridpede and finally Niveja Rojhlatine at sunrise.

As perhaps the world’s oldest religious community, the Yezidis have preserved an ancient tradition of extraordinary regard for heaven and earth alike, as well as respect, tolerance, and good will towards all other communities and religions of the world. Their ancient living heritage of life-affirming principles preserves deep truths that merit respect and emulation by all people of faith worldwide.

Charshema Sor - Red Wednesday

Yezidi New Year or Sere Sal falls on Charshema Sor or ‘Red Wednesday’, the first Wednesday after April 14th. These are the Charshema Sor (Sere Sal) dates for the years 2015-2020:

- 2015: April 15

- 2016: April 20

- 2017: April 19

- 2018: April 18

- 2019: April 17

- 2020: April 15

About the Authors

Nallein Satana al-Jilwah Sowilo is descended from a long line of magi or mai, the caste of ancient religious and ritual leaders who read the sacred Avesta and other chants, do pujas and practice divination and astrology. Born in the Yezidi holy village of Shingal, she was named Nallein Tiffany Sowilo at birth. At age 13, she received her spiritual name Yezidi al-Jilwah. She currently resides in Los Angeles, California where she teaches yoga and serves the Yezidi cause worldwide. Yezidi al-Jilwah is a practicing mai and offers puja services, Vedic astrology, Vedic gem stones consulting, gem stone sales, and mantras. She can be reached at lotussuns 'at' gmail dot com.

Patrick David Harrigan is a comparative religious scholar, author-photographer, publisher, and supporter of the Yezidi cause. He has lived for 25 years in the Indian subcontinent since 1970 and is conversant in German, Hindi-Urdu, Nepali, Tamil, and Sinhala. He did his undergraduate and master's studies in Asian languages & religion at the University of Michigan and did further post-graduate studies at University of California-Berkeley and at the University of Madras. He has published many articles and websites that showcase and explain the role of mythology in ancient religious beliefs and practices, especially concerning the pan-Indian wargod Skanda-Murugan and his multi-religious shrine in Kataragama, Sri Lanka. Following the latest assault by ISIS fighters against Yezidi shrines on Mount Sinjar, Yezidis urged Patrick to rush to Washington DC to meet the Baba Sheikh, spiritual leader of the Yezidi people, at the Murugan Temple of North America.

Patrick Harrigan and Nallein Satana al-Jilwah Sowilo now jointly compose and publish articles about Yezidi culture and religion. Visit the Yezidi Sanatana Dharma Society on Facebook to follow the cause of the Yezidis.

Photos courtesy of Eszter Spät and International Business Times of August 8, 2014

See also:

- Baba Sheikh’s Sere Sal New Year Message of Hope

- "Yezidi Places of Pilgrimage" by Eszter Spät

- "The Sanjak of the Peacock Angel" by Eszter Spät

- Photo Gallery: Iraq's Yazidi Kurds at Their Holiest Site, Lalesh Temple

|